|

Medical Imaging Interaction Toolkit

2016.11.0

Medical Imaging Interaction Toolkit

|

|

Medical Imaging Interaction Toolkit

2016.11.0

Medical Imaging Interaction Toolkit

|

Geometries are used to describe the geometrical properties of data objects in space and time.

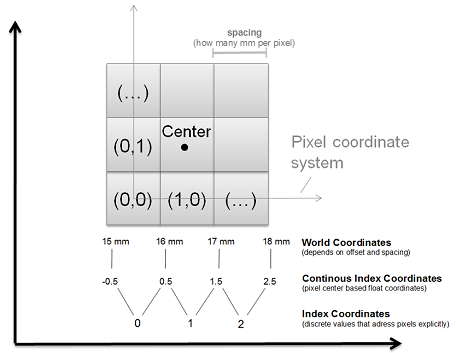

To use the geometry classes in the right way you have to understand the three different coordinate types present in MITK:

Like ITK, MITK differenciate between points and vectors. A point defines a position in a coordinate system while a vector is the distance between two points. Therefore points and vectors behave different if a coordinate transformation is applied. An offest in a coordinate transformation will affect a transformed point but not a vector.

An Example:

If two systems are given, which differ by a offset of (1,0,0). The point A(2,2,2) in system one will correspont to point A'(3,2,2) in the second system. But a vector a(2,2,2) will correspond to the vector a'(2,2,2).

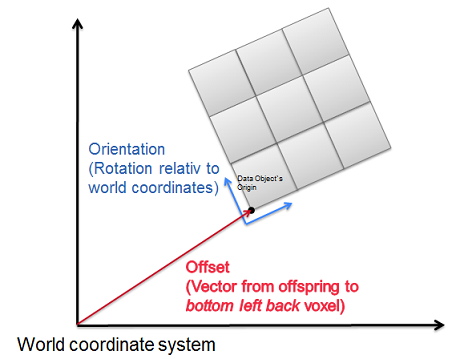

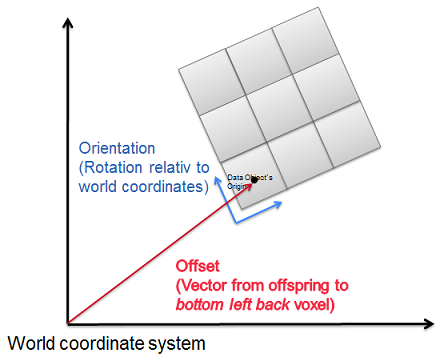

As the superclass of all MITK geometries BaseGeometry holds:

Every data object (sub-)class of BaseData has a TimeGeometry which is accessed by BaseData::GetTimeGeometry(). This TimeGeometry holds one or more BaseGeometry objects which describes the object at specific time points, e.g. provides conversion between world and index coordinates and contains bounding boxes covering the area in which the data are placed. There is the possibility of using different implementations of the abstract TimeGeometry class which may differ in how the time steps are saved and the times are calculated.

There are two ways to represent a time, either by a TimePointType or a TimeStepType. The first is similar to the continous index coordinates and defines a Time Point in milliseconds from timepoint zero. The second type is similar to index coordinates. These are discrete values which specify the number of the current time step going from 0 to GetNumberOfTimeSteps(). The conversion between a time point and a time step is done by calling the method TimeGeometry::TimeStepToTimePoint() or TimeGeometry::TimePointToTimeStep(). Note that the duration of a time step may differ from object to object, so in general it is better to calculate the corresponding time steps by using time points. Also the distance of the time steps does not need to be equidistant over time, it depends on the used TimeGeometry implementation.

Each TimeGeometry has a bounding box covering the whole area in which the corresponding object is situated during all time steps. This bounding box may be accessed by calling TimeGeometry::GetBoundingBoxInWorld() and is always in world coordinates. The bounding box is calculated from all time steps, to manually start this calculation process call TimeGeometry::Update(). The bounding box is not updated if the getter is called.

The TimeGeometry does not provide a transformation of world coordinates into image coordinates since each time step may has a different transformation. If a conversion between image and world is needed, the BaseGeometry for a specific time step or time point must be fetched either by TimeGeometry::GetGeometryForTimeStep() or TimeGeometry::GetGeometryForTimePoint() and then the conversion is calculated by using this geometry.

The TimeGeometry class is an abstract class therefore it is not possible to instantiate it. Instead a derived class must be used. Currently the only class that can be chosen is ProportionalTimeGeometry() which assumes that the time steps are ordered equidistant. To initialize an object with given geometries call ProportionalTimeGeometry::Initialize() with an existing BaseGeometry and the number of time steps. The given geometries will be copied and not referenced!

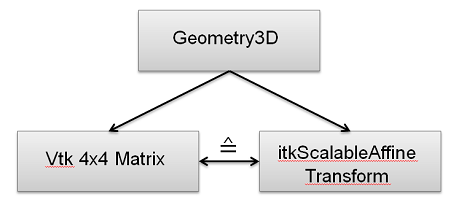

Also, the BaseGeometry is an abstract class and derived classes must be used. The most simple implementation, i.e. the one to one implementation of the BaseGeometry class, is the class Geometry3D.

SlicedGeometry3D is a sub-class of BaseGeometry, which describes data objects consisting of slices, e.g., objects of type Image (or SlicedData, which is the super-class of Image). Therefore, Image::GetTimeGeometry() will contain a list of SlicedGeometry3D instances. There is a special method SlicedData::GetSlicedGeometry(t) which directly returns

a SlicedGeometry3D to avoid the need of casting.

The class SlicedGeometry3D contains a list of PlaneGeometry objects describing the slices in the image.We have here spatial steps from 0 to GetSlices(). SlicedGeometry3D::InitializeEvenlySpaced (PlaneGeometry *planeGeometry, unsigned int slices) initializes a stack of slices with the same thickness, one starting at the position where the previous one ends.

PlaneGeometry provides methods for working with 2D manifolds (i.e., simply spoken, an object that can be described using a 2D coordinate-system) in 3D space.

For example it allows mapping of a 3D point on the 2D manifold using PlaneGeometry::Map().

Finally there is the AbstractTransformGeometry which describes a 2D manifold in 3D space, defined by a vtkAbstractTransform. It is a abstract superclass for arbitrary user defined geometries.

An example is the ThinPlateSplineCurvedGeometry.

Please read this section accurately if you are working with Images!

The definition of the position of the corners of an image is different than the one of other data objects:

As mentioned in the previous section, world coordinates of data objects (e.g. surfaces ) usually specify the bottom left back corner of an object.

In contrast to that a geometry of an Image is center-based, which means that the world coordinates of a voxel belonging to an image points to the center of that voxel. E.g:

If the origin of e.g. a surface lies at (15,10,0) in world coordinates, the origin`s world coordinates for an image are internally calculated like the following:

<center>(15-0.5*X-Spacing\n

10-0.5*Y-Spacing\n

0-0.5*Z-Spacing)\n</center>

If the image`s spacing is (x,y,z)=(1,1,3) then the corner coordinates are (14.5,9.5,-1.5).

If your geometry describes an image, the member variable isImageGeometry must be changed to true. This variable indicates also if your geometry is center-based or not.

The change can be done in two ways: